Music was a huge part of my childhood. It was one of the first things I heard, and not from the radio or a record player, but live, in the house. My father was a musician alongside his job as an engineer. He played in local bands, and even jammed with Mick Ronson. He played support to some big bands in the 70s too. Some of my earliest memories are of him playing his guitar in the front room – a room reserved for these instruments, all hanging in a row on the wall, and where we kids had to be quiet and well-behaved. I recall being fascinated by how his fingers, which moved so deftly across the strings, made that music. He tried to show me once but I couldn’t do it. Holding a pen was my way of creating that music.

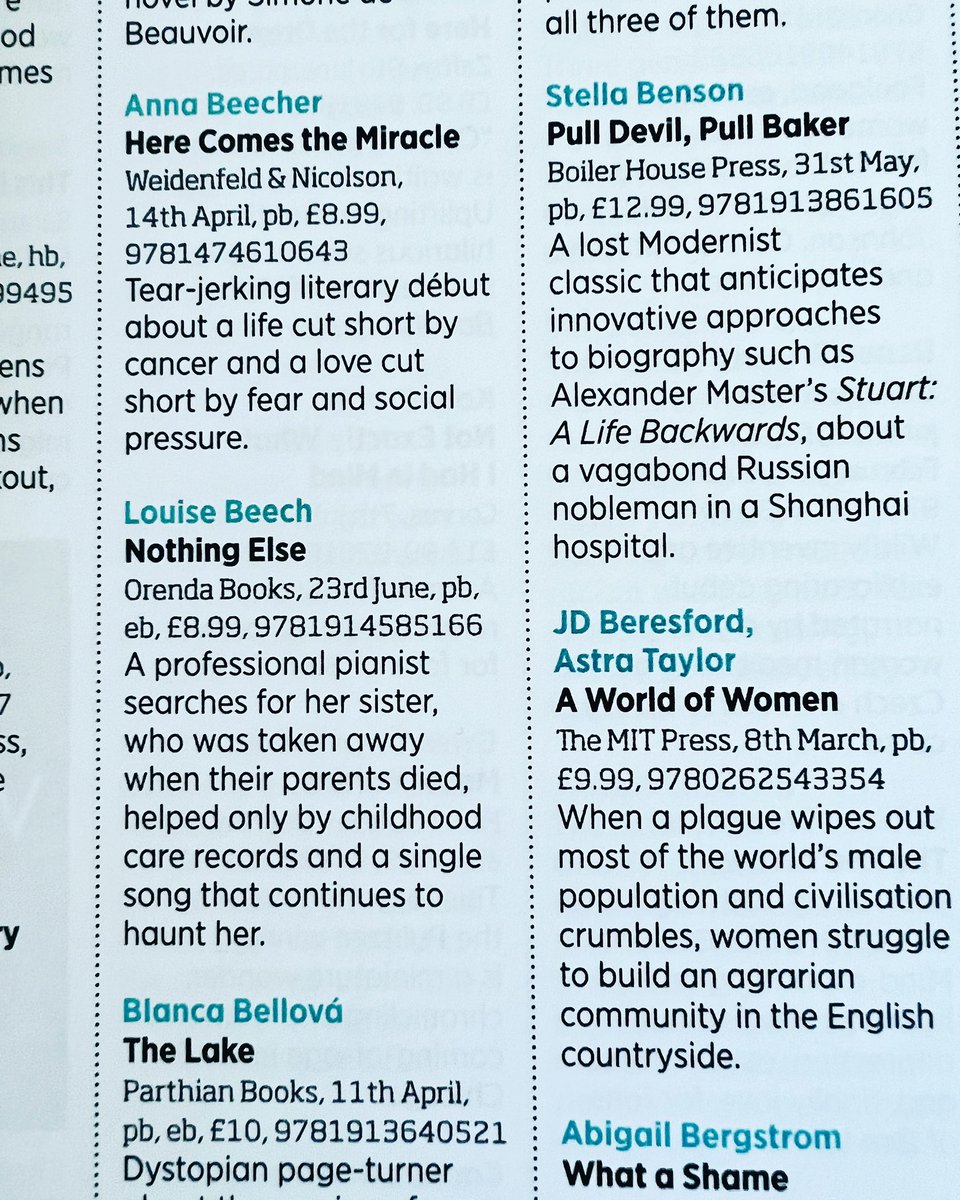

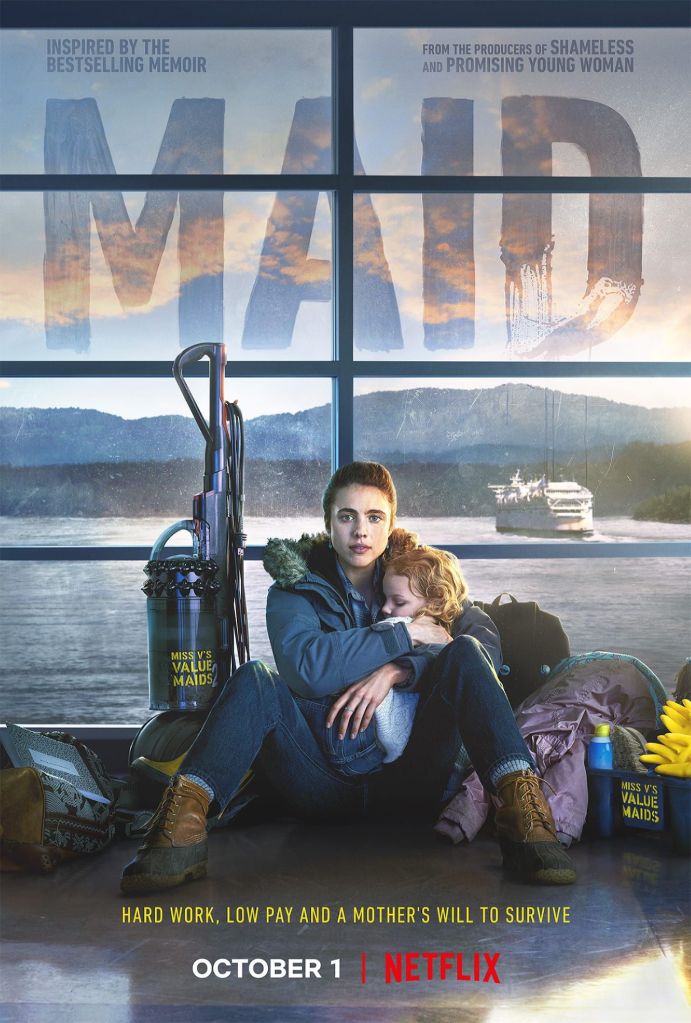

I learned early on how music could affect mood, what it maybe said about those playing it. Why they had chosen to listen that song, at that time. Was it to uplift, to escape, to drown out things they didn’t want to hear? The songs that my parents played in our house were varied, from my mother’s favourites like Abba and The Beatles, to my father’s choices, which were everything from pop to classical to rock to folk. This has made me very open-minded with music, giving everything a go. And it’s given me a deep appreciation of the power of it. Which is why I wrote Nothing Else, last year, during one of the many lockdowns. I wanted to explore how much music means to us, not only for pleasure and escape, but as a literal life-saver, as is the case with the story of Heather and Harriet, and their need to create a piece that drowns out the violence in their childhood home, a piece that doesn’t work when only one of them plays it. When they tragically lose one another after their parents die, they are haunted by this song, and long to find each another and play it together once again.

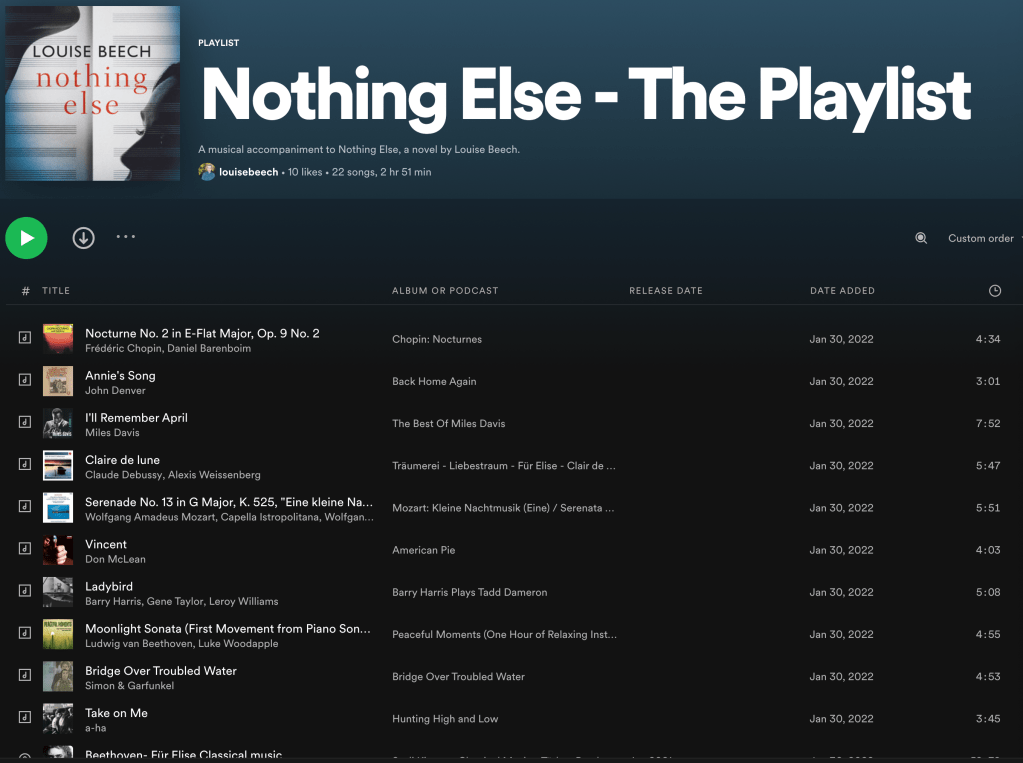

While writing Nothing Else, I created a playlist on Spotify of all the songs that are included in the book, some from the sets that Heather plays aboard the cruise ship, some from music she likes to listen to, some from the references to moments she is inspired. I found that listening to the music I was talking about created the mood I needed. Even on my morning walk, when I was trying to empty my mind and let the ideas in (how I always write, rather than plotting heavily), I listened to this playlist. I lived the music my characters were playing. Even when writing my less musical books, I always have a couple of albums that I play while I write, ones I later associate with that creation. It’s funny because I’ll hear those tracks years after and it will remind me of the fictional characters I invented as thought they’re real people. How about you? Do you need music when you write? Do you prefer silence? It’s always such a personal thing.